In my February column, I wrote about the fact that I had a stem cell transplant in early December 2019, about a month before I heard for the first time about the coronavirus.

The transplant entailed getting an unrelated donor’s stem cells to replace mine; then, if all went according to plan, these cells would grow into a new immune system to seek and destroy my cancer cells.

As a result of the transplant, all of my childhood vaccinations became ineffective. I was instructed to stay in isolation for at least four months in order to avoid infectious and possibly deadly diseases like influenza. Consequently, I have been quarantined since December.

Just a day before writing this, a friend told me that I’m a “trendsetter.”

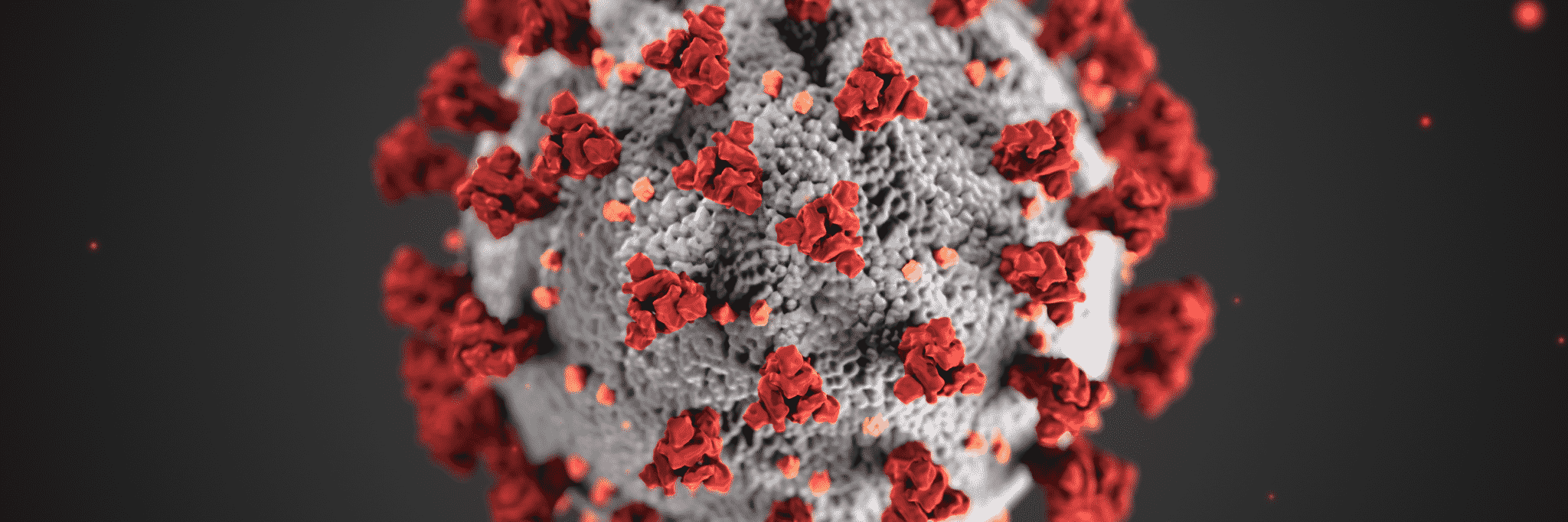

I knew very little about viruses before the coronavirus came along—only that they were microscopic infectious organisms that invade living cells and then reproduce. In an effort to review what I had been (mostly unconsciously) protected from before transplant, I Googled the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and found a piece entitled, “Vaccines for children: Diseases you almost forgot about.”

I was reminded that most of us had vaccines as children for some of the nastiest viruses, including polio, which invades the brain and spinal cord and leads to paralysis; tetanus, a potentially fatal disease that causes lockjaw; whooping cough, which can lead to violent coughing that makes it difficult to breathe; and many more.

Most older adults are familiar with chicken pox, mumps and measles. I had two of them as a young teenager. One that I forgot about is diphtheria, which affects breathing or swallowing and can lead to heart failure, paralysis and death. There are several more.

I imagined the panic that parents must have felt and the pain that young children must have experienced before vaccines were discovered to prevent these horrible infectious diseases.

For the time being, I cannot replace my old vaccines. I must wait for at least one year while my new immune system gets stronger.

The idea of being in isolation and maintaining a safe social distance for a few months post-transplant made sense to me. I was well prepared by doctors and nurses and I knew my wife would be a great caregiver, so I thought I could do the time.

And then, the coronavirus came along.

For me, being quarantined was an old hat by the time a national emergency was declared and everything started to shut down. I learned that this new virus’ main target was the lungs and people older than 60 years with underlying health conditions were its primary targets.

I fit the bill and knew that I’d have to do more time: at least another three months, my transplant doctor told me. The only difference is that this time, hundreds of millions of people would be joining me.

I was well-prepared before and after my transplant. I knew why I had to self-isolate and for how long. No one, including me, was prepared for COVID-19 and the mass quarantine that it now requires—not only to protect oneself and one’s family, but also to protect strangers. Mostly older strangers like me.

Scientists and other health professionals were the heroes of viral epidemics gone by. I do believe we will get through this, with people like immunologist Dr. Anthony Fauci leading the way.

Still, the unknown is what is most frightening. We all want answers, yet some remain illusive at the moment. This is an opportunity for all of us to strengthen our tolerance for ambiguity.

When will this end? No clue. Will it come back? No idea.

Although my new immune system needs more time to protect me, I just found out after a PET scan that I’m in complete remission from my cancer.

Will it come back? No idea.

We are all in the same boat, living in uncertainty, whether young or old, healthy or unwell. As Plato said, “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a harder battle.”

Andrew Malekoff is the executive director of North Shore Child and Family Guidance Center. To find out more, call 516-626-1971 or visit www.northshorechildguidance.org.