Guidance Center Hosts Spring ‘Lunch-In, Anton Media, April 7, 2021

Dr. Morris is a developmental psychologist whose research has focused on early childhood education. Recently, she has turned her attention to preventing suicide.

I always felt so blessed watching my boy-girl twins; even as teenagers they would walk arm in arm down the street, chatting and laughing together.

But that blessed feeling evaporated in June of 2019, when I lost my daughter, Frankie, to suicide, three weeks before her high school graduation. Ever since that day, I have thought of little else except how I could help the next struggling teenager, the next Frankie.

Several days after her passing, we opened our home up to our community, including Frankie’s very large group of teenage friends. It was a muggy June day, and the air conditioning was no match for the hundreds of people who came through our New York City apartment.

There was a momentary pause in the steady stream of people offering hugs and condolences when a parent of one of Frankie’s friends put her hand on my shoulder and said gently: “What strength Frankie had. It must have taken enormous energy for her to do what she did each day.”

That was Frankie. She had the strength to engage in school and in theater, despite her anxiety and depression. She had an ability to connect — emotionally, profoundly — with others, even when she was struggling herself. Her friends spoke to us of being caught off guard by her hugs or endearing comments. A teacher once described her as “empathy personified, with quite the fabulous earring collection.”

I like to think that some of her strength came from the home we tried to give her. Whether that strength came from her home or somewhere else, or both, Frankie just had a way of drawing out warmth wherever she went.

But like many who struggle with suicidal thinking, she kept her own pain camouflaged for a long time, perhaps for too long.

Suicidal thinking, whether it is the result of mental illness, stress, trauma or loss, is actually far more common and difficult to see than many of us realize. A June 2020 Centers for Disease Control survey found that one in four 18- to 24-year-olds reported that they had seriously thought about taking their lives in the past 30 days; prepandemic estimates found that just under one in five high schoolers had seriously considered suicide, and just under one in 10 had made at least one suicide attempt during the previous year.

That’s a whole lot of kids. And some, like Frankie, are able to muster the energy to make their struggle almost invisible. Despite 50 years of research, predicting death by suicide is still nearly impossible. And with suicidal thinking common, suicide remains the second leading cause of death among 15- to 24-year-olds, after accidents.

Like others who have lost a child to suicide, I have spent countless hours going over relentless “what ifs.” And because I am a developmental psychologist who specializes in prevention programs, my “what ifs” also include the ways the world might look different so that another family won’t experience our fate.

One day while driving on a familiar stretch of highway with “what ifs” swirling in my head, I saw a sign flash “Click it or Ticket.” It struck me: Maybe what we need are seatbelts for suicide.

“Click it or Ticket” was born in part out of a concern in the 1980s about teenagers dying in car accidents. Just as with suicides today, adults couldn’t predict who would get into a car accident, and one of the best solutions we had — seatbelts — was used routinely, in some estimates, by only 15 percent of the population. Indeed, as children, my siblings and I used to make a game of rolling around in the back of our car, seatbelts ignored.

Three decades later, our world is unlike anything I could have imagined as a child. Putting on a seatbelt is the first lesson of driver’s education; cars get inspected annually for working seatbelts; car companies embed those annoying beeping sounds to remind you to buckle your seatbelt; and for added measure, highway signs flash that “Click it or Ticket” message as part of a National Highway Traffic Safety Administration campaign. The result? Most of us (estimates range as high as 91 percent) now wear a seatbelt.

What would it look like if we had an approach to suicide akin to universal seatbelt safety, starting early in adolescence?

Just as my parents couldn’t predict in the 1980s what seatbelt safety would look like now, I am not sure what suicide prevention should look like in the future. But I imagine a world in which every health worker, school professional, employer and religious leader can recognize the signs of suicidal thinking and know how to ask about it, respond to it and offer resources to someone who is struggling. Just as today we all know to dial 9-1-1 in an emergency (a system that came into being in the late 1960s), we would all know the national suicide prevention hotline (1-800-273-TALK, which will also be reachable at 9-8-8 in 2022) and text line (text HOME to 741741). We would “suicide-proof” our homes by locking up handguns, lethal medications and other things teenagers can use to harm themselves. And families would ask their children often about suicidal thinking.

When I told Frankie’s orthodontist about her suicide, his response surprised me: “We really don’t come across that in our practice.” Even though orthodontists don’t ask about it, they see children during their early teenage years, when suicidal thinking often begins to emerge. Can you imagine a world in which signs for the prevention hotline and text line are posted for kids to see as they get their braces adjusted? Or one with pamphlets in waiting rooms that instructed parents about suicide’s warning signs?

What if the annual teenage pediatric checkup involved a discussion of one-at-a-time pill packaging and boxes to lock up lethal medications, the way there is a discussion of baby-proofing homes when children start to crawl? What if pediatricians handed each adolescent a card with the prevention hotline on it (or better yet, if companies preprogrammed that number into cellphones) and the pediatrician talked through what happens when a teenager calls? What if doctors coached parents on how to ask their teenager, “Are you thinking about suicide?”

What if we required and funded every school to put in place one of the existing programs that train teachers and other school professionals to be a resource for struggling students? A number of states mandate training in suicide prevention, some as part of the Jason Flatt Act. States like New York and California (along with 13 others) encourage, but do not mandate, such programming. A few, like Rhode Island (which incidentally has the lowest teenage suicide rate in the nation), have no mandate but have still managed to pair training of teachers with resources for students, who are often the first to notice the signs of suicidal thinking in their friends.

But doesn’t asking about suicide put the idea in a kid’s head? Nope. Scientists at Columbia University have shown that it does not make them more suicidal, findings that were confirmed in a recent meta-analysis across studies of adolescents and adults. While it’s true that safe messaging about suicide matters, asking about suicide among adolescents does not increase their risk.

I recognize that despite progress identifying effective programs to combat suicidal thinking, their success rate and simplicity does not compare with what we see with seatbelts. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do more.

Part of doing more also includes making the world more just and caring. To give one example, state-level same-sex-marriage policies that were in place before the Supreme Court legalizedsame-sex marriage nationally have been linked to reductions in suicide attempts among adolescents, especially among sexual minorities. Just as safer highways and car models make seatbelts more effective, asking about and responding to suicidal thinking is only one part of a solution that also includes attention to societal injustices.

I understand, of course, that asking about suicidal thinking is scary. But if it is scary for you to ask about it, it is even scarier for the teenager who is thinking about it.

I will never forget sitting with Frankie in the waiting room in the pediatric psychiatric wing on the night I brought her to the inpatient unit, three months before she took her life. We had been there for hours, seeing one group of doctors and then another. A nice nurse had given us some apple juice and granola bars. Sipping from those child-size juice boxes and munching on one of the granola bars, Frankie turned to me and said, softly, almost in a whisper, “You know, I am so glad you finally know.” I could hear the relief in her voice. I just nodded, understandingly, but it broke my heart that she held on to such a painful secret for so long.

How do we build a more supportive world for our children? I find myself inspired by Frankie’s teenage friends, who cared deeply for her and now support one another after her passing.

During high school, Frankie found warmth and healing in the theater program office, tucked behind a door in a bustling New York City public school. On good days, she would sit on the worn couch in that office, snuggle in a pile of teenagers and discuss plays, schoolwork and their lives. On hard days, she would hide in an untraveled corner of that same office and allow the anxiety and depression to run its course. And in that corner space, she would text a friend to help her get to class or, after she had opened up about her struggles, encourage others to open up as well.

The fall after Frankie left us, some students decided to remake that hidden corner, dotting the walls with colored Post-it notes. Scrawled on a pink Post-it were the words “you matter”; a yellow one read “it gets better”; an orange one shared a cellphone number to call for help. Tiny Post-it squares had transformed the corner into a space to comfort, heal and support the next struggling teenager.

I don’t know if a seatbelt approach would have saved Frankie. And I understand that all the details of such an approach aren’t fully worked out here. But I don’t want us to lose any more children because we weren’t brave enough to take on something that scares us, something we don’t fully understand, something that is much more prevalent than many of us realize.

If 17- and 18-year-olds who’ve lost a friend have the strength to imagine a world dotted with healing, then the least we can do as adults is design and build the structure to support them.

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (TALK). You can find a list of additional resources at SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources.

Pamela Morris (@pamela_a_morris) is a professor of applied psychology at NYU’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development.

If your child or teen is expressing suicidal thoughts or feelings, we can help through our Douglas S. Feldman Suicide Prevention Project. To learn more, click here.

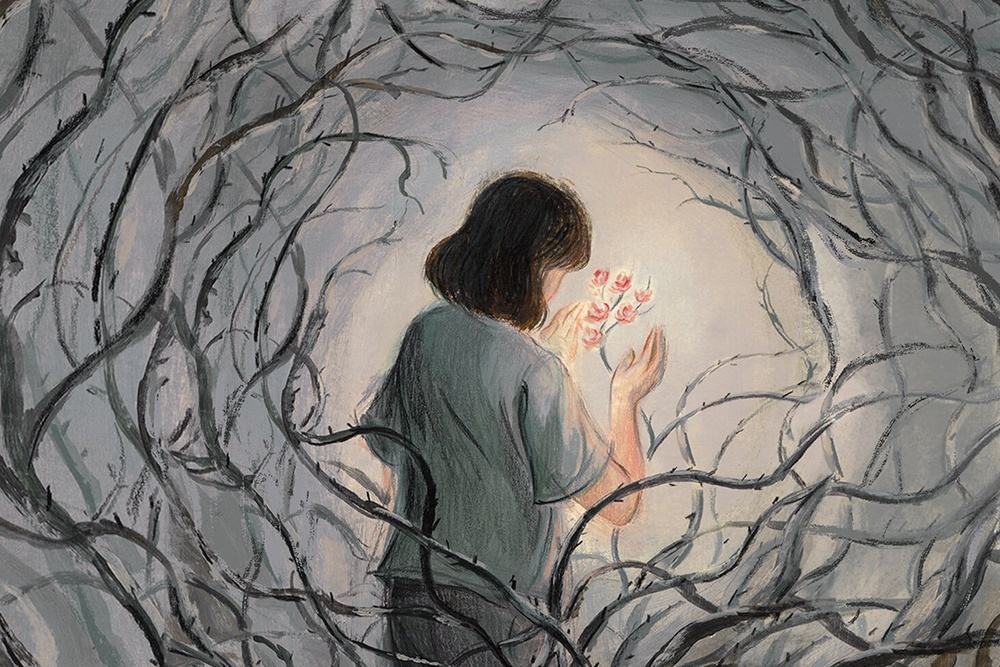

Illustration by Sally Deng

As children return to classrooms and playgrounds, and maybe soon to summer camp, we must not forget that many are still feeling the effects of the social isolation they experienced when school went virtual last year. Learning is still remote for many kids, who continue to be cut off from treasured spaces that nurture positive, developing relationships, caring about others, thinking critically and avoiding negative behaviors.

Even though the physical settings might be restored, many children continue to feel an undermined sense of security. Some will be resilient and bounce back. Others will need extra support from parents and adults in their community.

Mental health workers are seeing young people in their second decade of life who are anxious and depressed. These include both kids who were struggling with their mental health before the pandemic and those who were stellar students with rich social lives who seem to have fallen off the coronavirus cliff.

The unforeseen loss of routine is especially impactful on young folks like these for whom connecting with peers is so integral to their daily life experience. Now, and since the onset of the pandemic, it’s as if the adolescent ecosystem has suddenly been deprived of oxygen and light.

For far too many young people, this is a painful time when an essential aspect of their lives has been suddenly threatened, resulting in lost connections, isolation and longing. This is a lonely time in which the grief they experience is unacknowledged and unsupported by any social ritual, a demoralizing reality that may lead to days and nights of anxiety, desperation and, for some, deep depression and dark thoughts about whether life is worth living even one more day.

Although this may be a time to draw closer to one’s family, the notion of increasing togetherness with parents at the precise time in one’s life that a young person is striving to become more independent can create an existential crisis. Parental support should include encouraging social connection outside the family, either virtually or in safe face-to-face settings. This does not suggest pushing away one’s child, but rather empathizing with the healthy need for some separation and peer connection. Groups of peers can create the sparks necessary to ignite the warm fires of intimacy that will help see many a young person through this public health disaster.

Adults need to understand the uncertainty and shakiness that kids might be feeling. Reinforce to them that you are there for them, that we all went through a very difficult time and there will be more tough times ahead in life, but that you will always stand by their side.

What we know is that young people who feel connected are less likely to engage in high-risk behaviors such as self-harm, violence, early sexual activity or suicidal actions. As my friend and colleague Dr. Ariel Botta, a group worker at Boston Children’s Hospital, advised: “Healthy human development and adjustment require both connection and solitude. At this point in history, there is plenty of isolation and a dire shortage of connection.”

The importance of attachment and connection carries on throughout a child’s life and impacts relationships as they move into adulthood. The support you give them is not just for now — it’s forever.

Andrew Malekoff is the executive director of North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center in Roslyn Heights.

Photo Credit: Getty Images/Marko Geber

There has been a growing concern about the surge of racial violence, hateful incidents and discrimination against people of Asian descent in the U.S. amid the COVID-19 pandemic. A new study released by Stop AAPI Hate showed that there were nearly 3,800 incidents targeting Asians in the U.S. in the past year alone.

This has only intensified after a gunman killed six Asian women and two others in senseless attacks on spas in Atlanta on March 16. Although uncertainty remains about whether the perpetrator will be charged with a hate crime as well as murder, the killing spree became a flash point, leading to nationwide protests to #StopAsianHate.

According to U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, “The pandemic continues to unleash a tsunami of hate and xenophobia, scapegoating and scare-mongering.” He asked governments worldwide to take action “to strengthen the immunity of our societies against the virus of hate.”

A week before the mass shootings in Atlanta, at a March 8 forum on anti-Asian racism, Chinese American activist and journalist Helen Zia said, “We have seen this terrible nightmare before.” She recounted some of the brutal milestones, beginning with the interning of Japanese Americans during World War II from 1942-1945, an episode that has long been considered one of the most dreadful violations of American civil rights in the 20th century.

Forty years later, in 1982, Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American draftsman, was murdered in Detroit by two white men who worked in a Chrysler plant. Asian Americans of all backgrounds were targeted when automakers from Japan that were producing more fuel-efficient cars were blamed for layoffs.

Looking back, “people knew from personal experience that we were lumped together,” said Zia. “But in terms of identifying as pan-Asian, the key thing was that a man was killed because they thought he looked like a different ethnicity.”

In the U.S. there is no concrete governmental response toward protecting people of Asian descent from pandemic-fueled racist attacks, despite their growing number. During the Trump administration, slurs like “Wuhan virus” and “Kung Flu” were routinely used even at the highest levels of government. When officials used the term “China virus” it was never purely descriptive and always pejorative.

It was recently brought to my attention by a concerned parent that a 5-year-old Asian American child on Long Island was on the receiving end of a coronavirus-driven tirade while playing in a park. The child was left in a state of shock, not fully understanding why a perfect stranger, an adult, was raging at him.

Parents are worried about racially motivated attacks ranging from teasing to physical confrontations against Asian American students when schools fully reopen in the fall. They want to know if their children will be returning to a safe environment.

Historically, immigrant communities have been singled out in times of public health crises. Their passages to the U.S. have been given derogatory labels such as “plague” and “invasion,” objectifying migrants as infected, dirty and carriers of disease.

In her new book “Caste,” Isabel Wilkerson cites anthropologists Audrey and Brian Smedley who explain, “We think we ‘see’ race when we encounter certain physical difference among people such as skin color, eye shape and hair texture. What we actually ‘see’ are the learned social meanings, the stereotypes that have been linked to those physical features by the ideology of race and the historical legacy it has left us.” Indeed, most of the attacks against people of Asian descent in America are not against Chinese but anyone who looks East Asian.

Law enforcement surveillance and vigilance is necessary; however, nothing less than what Wilkerson calls “radical empathy” will lead to lasting change — “the kindred connection from a place of deep knowing that opens your spirit to the pain of another as they perceive it.”

Only our solidarity with those who are targeted will prevent community spread. We must all stand tall and together against the toxic pandemic of racism, whether individual or systemic.

Andrew Malekoff of Long Beach is executive director and CEO of North Shore Child and Family Guidance Center, a nonprofit children’s mental health agency on Long Island.

As we reach the end of National Social Work month, which runs through March, we want to take the opportunity to thank our wonderful staff at North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center, which consists of social workers, mental health counselors, psychologists, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, all of whom devote themselves to the children and families they serve.

Following are thoughts from some of our dedicated staff members on why they chose to work in the mental health field, making a difference every day of the year!

Although my undergraduate school major was economics and I thought I was headed for a career in big business, I chose to pursue a career in social work after working as a volunteer, first as a Big Brother with a couple of school-age kids while at Rutgers University in the early 1970s. About a year after I graduated, I joined Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) and worked with teenaged boys and girls in a low-income Mexican-American community in Grand Island, Nebraska. After spending three years in Nebraska, I knew I had to go back to school if I wished to pursue this kind of work as a career. After some research, I thought the social work field suited me best because of its values. Social work didn’t only see troubled kids as broken objects to be fixed, but as whole persons with assets and strengths. It recognized one’s environment as a critical influencing factor in their life—for good and bad. And, finally, social work believed in self- determination, human dignity and social justice. It was a good fit. – Andrew Malekoff, LCSW

“Blessed are the flexible for they shall not get bent out of shape.”

We are living in a time of unprecedented chaos and transitions; our children and families are in search of an accepting, calming environment to strengthen their skills and successfully overcome challenges. As therapists we can provide a much-needed safety net and take a transformative place in role modeling effective communication, adaptive self-care and mental health wellness in children and families. It is a privilege and a passion to continue my journey as a Mental Health Counselor. – Hillary McGrath, LMHC

The past year has highlighted the importance of mental health services and support for our society. As social workers, we’ve known this for a long time, and I think it’s a reason that many of us have chosen to do this work. It’s not easy work, and it’s often undervalued, but the reward that comes from making a difference in the life a child or their family is what keeps me going. – Vanessa McMullan, LCSW

“Social work didn’t only see troubled kids as broken objects to be fixed, but as whole persons with assets and strengths.”

I chose social work after realizing that no matter where I worked or in what role, I always wanted every person I spoke with to feel like no matter what issue they had at the time, someone was in it with them. There’s no stop sign on your corner? That is concerning, let’s call public works together! Not enough crunch topping on your ice cream cone? Maddening! Let’s see what we can do. (Yes, I was fired from TCBY). I got my Master’s in social work as my third degree. I have worked as a journalist, supervised a long-distance learning department and managed a local radio station. I worked in various settings, from a run-down office in Southern Brooklyn to a posh corner suite on Wall Street. It was never quite right, and whatever I did never seemed enough. Working with children and families is special; so much of our understanding of the world and ourselves comes from the experiences from our family system. Small changes at home can really generate positive impact in other areas of our lives, especially for little ones. – Laura Mauceri, LCSW

After I started my Master’s degree, I knew right away that I would do clinical work. If only I can help people tolerate their distress and contribute to their better mental state by being empathic, listening to what they go through, teaching them coping skills and sharing my positive energy. They say, “Better late than never.” I am very thankful to my new profession which allows me to contribute to others and wake up every day knowing that I can make a difference. – Masha Leder, LMSW

“Having chosen the career pathway to work with children and families has proven to be both invaluable and rewarding during these unprecedented times.”

A career in social work provided me the choice of working in a multitude of settings. Counseling is a rewarding practice, as this service can improve outcomes for children, families and their communities. I have always valued the importance of a stable family unit. Having chosen the career pathway to work with children and families has proven to be both invaluable and rewarding during these unprecedented times. All children deserve the opportunity to thrive throughout their lifetime, and I am proud to foster their success. – Julia Bassin, LMSW

I wanted to be a social worker and to work with adolescents and families because I had hoped to become a trusted person that youth could connect with and let inside their world. Having children and teens open up and share their inner feelings and experiences during the most challenging times in their lives is an honor and a privilege. – Brooke Hambrecht, LMSW

“Small changes at home can really generate positive impact in other areas of our lives, especially for little ones.”

In retrospect, there was nothing I wanted to do more than to become an agent of change, and I found that in social work. One could say that social work found me! As I went through my years within the social work field and up to the day I decided to complete my Master’s in social work, I found that my passion lied specifically in working with children and families. That is where I felt that I would have the most impact to make change possible. Families live, grow and heal together, so why not be present for these struggles, changes and achievements to support families in seeing the end of their own rainbow? – Edenny Cruz, LCSW

I have no children of my own, and it is heartache, but I feel good about them and me when I reach out to these little ones and see them grow. I am in the fight to save as many lives as I can during this season. – Ruthellen Trimmer, Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner

“I am very thankful to my new profession which allows me to contribute to others and wake up every day knowing that I can make a difference.”

I entered the world of social service post undergrad due to my own personal experience with individual therapy and watching my own family navigate various systems of care for my older sister who is diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy, and my father who was diagnosed with a terminal illness early on in his life. I spent five years working with adults with a variety of psychiatric diagnosis in various settings prior to return to school to obtain my Master’s in social work. The turning point to obtain this degree for me very much had to do with wanting additional knowledge and training to have more accessibility to other settings of care. My supervisor during my first clinical placement said something to me that made me pivot to working with children. She said, “Whenever I have felt complacent or that I was overly knowledgeable in an area, I have challenged myself and changed the populations or setting I was working in.” Perhaps she sensed my complacency in the adult mental health world at the time. This is what led me to request that my second clinical internship be with young children and families. That was a defining moment for me, and I have been working with children and families since. I didn’t know it then, but I most certainly know now, that this is in fact my calling: to help children and families heal with an array of challenges and dynamics that this life presents. I take pride in wearing this title and continuing to improve my practice. –Gillian Pipia, LCSW

I went into psychiatric nursing with children because I always liked working with children and their families. I like getting to know people in a more intimate and involved way. The relationships are ongoing and meaningful for the time that you are with them. It is rewarding and gratifying to see them move on and make progress. I am happy to be a part of that. – D.S., Psychiatric Nurse