by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Dec 7, 2022 | Ask The Guidance Center Experts, Blank Slate Media, Blog, In The Media

Ask the Guidance Center Experts, December 6, 2022

In this monthly column, therapists from North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center answer your questions on issues related to parenting, mental health and children’s well-being. To submit a question, email communications@northshorechildguidance.org.

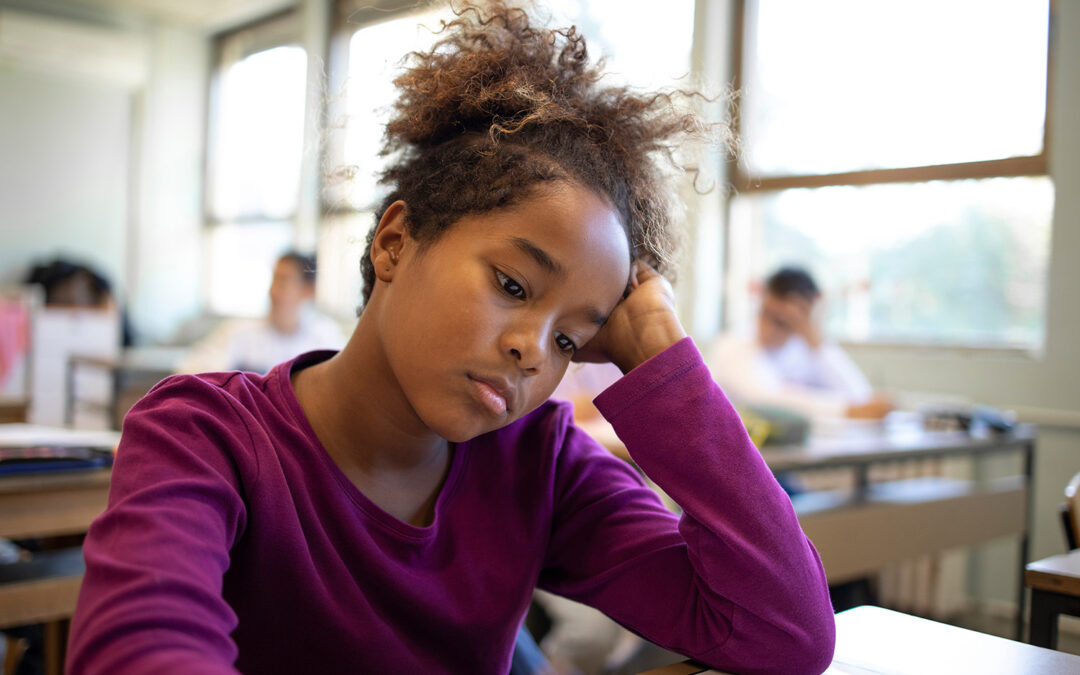

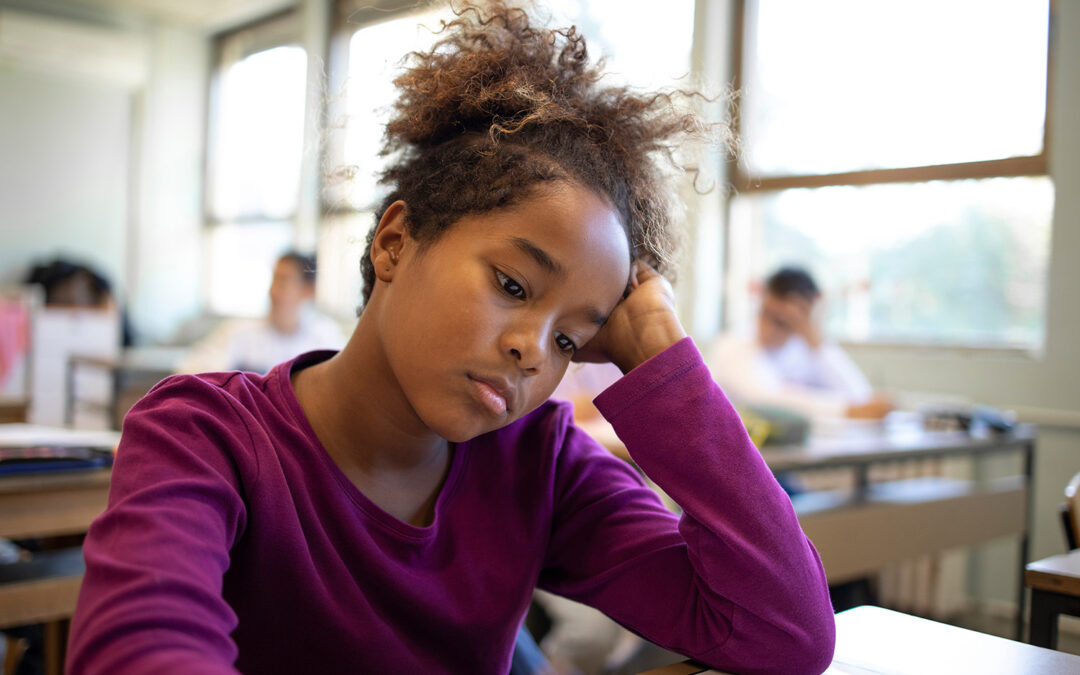

Question: My son is begging my wife and me to get him a dog for the holidays. We both grew up having dogs in our homes and found it to be very rewarding. But we also know that it’s a lot of work and takes a big commitment to care for a pet – especially a dog! We are inclined to say yes, especially since the pandemic left him feeling pretty low, and we hope this will lift his spirits. Plus, he promises he’ll take on the bulk of the responsibility. What do you think we should do?

— Pet Parenting Puzzle

Dear Anxious Parents: You are wise to take this decision very seriously. Dogs, as well as other pets, do require a lot of care, and if you are lucky, they will be part of your family for many years to come.

You’re also right in realizing that pets can offer many mental health benefits for kids. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, developing loving feelings about pets can contribute to a child’s self-confidence. Positive relationships with pets can aid in the development of trusting relationships with others. And a good relationship with a pet can help in developing non-verbal communication, compassion and empathy.

Some other benefits: Having pets leads to an increase in physical activity; reduces stress; provides companionship and social support; and fosters a connection with the natural world.

Pets provide unconditional love, which is important for every child, but especially helpful for kids who are having difficulties with depression, anxiety and low self-esteem. In fact, research indicates that children with pets tend to have higher levels of self-worth compared to those who don’t have animals. They can also help children with issues such as shyness and autism with their social skills.

All kids, whether or not they have mental health challenges, benefit from their relationships with animals, but if you are considering bringing a pet into your family, here are some factors to consider:

- Kids will promise the moon and stars to get a pet, but as the adult, you are likely to be the one who does most of the caretaking, so make sure you are ready for the responsibility.

- Take finances into consideration. Caring for pets can be an expensive proposition, with estimates running from $500 to well over $1,000 each year.

- Do you have little ones in the house? Children under three or four need to be supervised with pets at all times, since they may be impulsive and risk harming the pet or themselves.

- When choosing a pet, do your research. The pet should be a good match for your lifestyle. For example, if you live in an apartment, you might want to avoid getting a highly active dog. But if you have a fenced-in yard and enjoy tossing the ball around, an energetic pup may be the right fit.

- Are you out of the house for a large part of the day? Pets require care and love, so if you and your family aren’t home most of the time, a dog or even a cat might not be the right pet for you.

- Do your kids have asthma or other allergies? Despite the hype, there really are no allergy-free cats or dogs—but there are some breeds that are less allergenic than others. Ask your vet for suggestions.

Adopting from a shelter is a great way to save the life of an animal. If you decide that you want a specific breed or your heart is set on the type of dog you had as a kid, consider a rescue or shelter pet. Either way, always make sure you speak with the shelter or breeder about the individual history and personality of your prospective pet. Everything is not always apparent when a fury creature is first introduced at a visit.

Whatever you decide, we wish you and your family a happy and healthy holiday!

North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center, Long Island’s leading children’s mental health organization, is seeing clients both remotely via telehealth platforms and in person, depending on the clients’ needs. No one is ever turned away for inability to pay. To make an appointment, call 516-626-1971 or email intake@northshorechildguidance.org.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Dec 5, 2022 | Blog

At North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center, our promise is to see children from birth through age 24. In the last year, we have served an increasing number of young children who have experienced enormous trauma due to the pandemic.

Thankfully, we have a dedicated team of therapists who are specially trained to work with our youngest clients, employing creative approaches that help little ones move from hurting to healing.

We wanted to share with you a beautiful letter and drawing we received from one of those youngsters, a girl named Elaina.

We’ll let her words and images tell the story.

All of us at the Guidance Center are so grateful to all of you who support our work. Because we never turn anyone away for inability to pay, we count on your generosity to help us give children like Elaina the help they need to bring joy back into their young lives.

Thank you for caring for kids!

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Nov 28, 2022 | Blog

Congratulations! You’ve survived the whirlwind of Black Friday, Small Business Saturday and Cyber Monday. Phew! First, take some time to enjoy the outdoors with your family, maybe jumping in some piles of leaves with your little one!

But after that, remember that today is the day to do something to make you feel good while doing good for others!

Today is Giving Tuesday, when people across the globe join together to make the world a better place.

On this special day, please support the mental health of the children and families in your community by donating as generously as possible to North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center.

But don’t stop there!

From Thursday Dec. 1 through Saturday Dec. 3, shop at Americana Manhasset’s Champions for Charity® and designate North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center as your charity of choice! 25% of your designated full-price, pre-tax purchases will be donated back to us! Select stores at Wheatley Plaza also take part. Simply register for your Champion Number (It’s free) at championsforcharity.org and present it at the time of each purchase.

Finally, don’t forget to shop year-round through AmazonSmile at no extra cost to you. Just click on North Shore Child & Family Guidance Association here to register us as your charity of choice.

Thank you!

Why Support the Guidance Center?

Below are some comments from some of our most dedicated donors about why they spend their philanthropic dollars to support the Guidance Center’s mission.

Rosemarie and Mitchell Klipper

Rosemarie and Mitchell Klipper

The connection between Board Member Rosemarie Klipper and the Guidance Center has been a strong one for many years, as she and her husband Mitchell are always giving of their time, financial resources and creative ideas. “As you give to others, you’re helping yourself as well,” says Rosemarie. “It’s a wonderful feeling to be able to make a difference in peoples’ lives. I encourage everyone to get involved by giving to such a wonderful organization as the Guidance Center.”

Andrea and Michael Leeds

Andrea and Michael Leeds

Board Member Andrea Leeds and her husband Michael are longtime devoted supporters who continually amaze us with their dedication to our work. “The Guidance Center’s programs continue to grow to meet the needs of children dealing with difficult personal issues like depression, anxiety, bullying and so many others,” says Andrea. “The mission is more important now than ever during the COVID crisis, with illness, death and trauma having a devastating impact on the children and families in our community.”

National Grid volunteers work on our Nature Nurser

National Grid

“We know mental health is so important to all in our community, and it’s key to have places like the Guidance Center to help families and children on Long Island,” says National Grid’s Kathy Wisnewski. “National Grid is dedicated to investing in our youth, and we want to make sure we are doing everything we can to support the mental health of the next generation of leaders.”

Daniel Donnelly

Dan Donnelly

Dan Donnelly says that the work the Guidance Center does for children on Long Island is what motivates him to be such a dedicated supporter. But he also credits his admiration for the staff. “The people you have working here are such caring souls,” he says. “Life is about people and connecting. The relationships that I have with the Guidance Center staff and support team are one of the reasons why I stay involved.”

Jane and Marty Schwartz

Jane Schwartz

Our former Board President Jane Schwartz has been a dedicated friend and supporter of the Guidance Center for more than five decades. “The Guidance Center “provides a wonderful service to the Long Island community, with caring, dedicated staff members and a Board of Directors that are so devoted to helping all children and families, including those who cannot afford to pay for services.”

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Nov 22, 2022 | Blog

November is National Gratitude Month, and we asked our staff members to tell us what they are grateful for.

North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center is grateful for all of you who support our work during this holiday season and throughout the year. Your generosity is the reason we have been able to bring hope and healing to the children and families of Long Island for nearly 70 years.

Thank you, and have a very Happy Thanksgiving!

I’m grateful for being able to partake in my passion of traveling to different countries again and embracing their beauty. – Kathy Rivera, Executive Director/CEO

I am grateful for many things, one being my family. When I was younger, I was diagnosed with HPV and was told I might never be able to have kids. Today I am happily married and a mother of three beautiful children. I am forever grateful to God for giving the beautiful gift of being a mother; they are my strength and fill my life with so much joy every day. I am also grateful for my husband who is an extraordinary partner and amazing father to our children. And last but not least, I am grateful for both my mother and mother-in-law who are still with us and get to see their grandkids grow. – Joselyn Alberto, Assistant to the Director of Outpatient Operations, Regulatory Compliance & Quality Assurance Officer

I am grateful for nature and overall, the fall season. November is actually my favorite month for many reasons. Some of them being trees (I take many, many pictures of them), spending time with family on thanksgiving, and it’s also my birthday month! – Evelyn Turcios, Bilingual Social Worker

I’m grateful for my family! – Holly Abro, Therapist

I’m grateful for my loving husband who is supportive, helpful, and loves me for who I am. I’m also grateful for my fur baby, Spike. Spike suffered through a severe case of Pancreatitis several months ago and we didn’t know if he was going to survive. I am so grateful for God giving me more time with my fur baby Spike. I am more appreciative of Spike than ever before after almost losing him. Spike is emotionally supportive for me and loves me more than he loves himself! He’s my best friend – he’s family! – Lucille Buscemi, Peer Recovery Specialist

I am grateful for my family, friends and supportive work colleagues. – Dr. Sue Cohen, Director of Early Childhood & Psychological Services

I am grateful for all the wonderful and talented people who make working here at the Guidance Center such a privilege! – Lauren McGowan, Director of Development

I am grateful to be a daughter/caregiver to this lovely lady who is 84 years old and blind. Doesn’t she look lovely? -Dr. Nellie Taylor-Walthrust, Director of the Leeds Place

My 10-year-old puppy, Lucy, who greets me with such joy each day, gives me reason to be grateful every day of the year. – Jenna Kern-Rugile, Director of Development

I am grateful for my relationship with God, my boys, home, job, dancing hobby and health! – Monica Doyley, Head Teacher, Children’s Center at Nassau County Family Court

I’m grateful for my siblings. – Stacy Brief, Therapist

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Nov 14, 2022 | Blog, Donor Profile

While financial donations are crucial to making our work at the Guidance Center possible, there are several other ways to contribute to our lifesaving mission.

Case in point: our wonderful community partners at National Grid, an electricity, natural gas and clean energy delivery company serving more than 20 million people across New York and Massachusetts.

Kathy Wisnewski

Kathy Wisnewski, Long Island Regional Director, Community Customer Management, says that National Grid has a long and proud history of volunteerism. “We’ve always been dedicated to having an impact on the communities where we live and work,” she says.

Project C

Though National Grid’s volunteer efforts at nonprofits, parks, businesses and other locations have been going on for many years, the utility officially launched what it calls “Project C” in 2021.

According to Wisnewski, Project C is designed to go beyond the utility’s work in the energy sector and to inspire positive change, create positive impact in our neighborhoods and strengthen communities for years to come.

In addition to volunteerism, Project C focuses on four key priorities: clean energy and sustainability; workforce development; neighborhood investment and community engagement; and environmental justice and social equity.

A dedicated group of National Grid employees (pictured here with Guidance Center staff) did an amazing job sprucing up our Nature Nursery.

Inspiring Future Leaders

The Guidance Center’s partnership with National Grid began in February 2019, when we hosted a Career Day at Nassau B.O.C.E.S. High School in Wantagh.

Juan Santiago, National Grid Customer and Community Manager, won over the students, sharing that he wasn’t that interested in academics as a youth but found his way with a little faith and hard work. “Just because someone doesn’t take a traditional route doesn’t mean they are any less motivated,” he told the audience. “There are many paths to success, and if you put your hearts and minds into it, you can do anything!”

Our next collaboration took place that March, when National Grid employees Sarah Kahrs and Paula Gendreau generously donated their time and expertise to coach students in a Mock Interview Day at Nassau B.O.C.E.S.

“This event was an incredible experience,” says Kahrs. “It was so exciting to be able to take an active role in helping these young adults prepare for their future.”

Gendreau adds, “I was impressed by all the positive energy! I was fortunate to meet some great candidates, and it was my pleasure to be part of a wonderful day.”

As spring 2019 arrived, we welcomed seven National Grid employees to our Leeds Place in Westbury, where they spent the day planting and painting our signpost, giving the building a fresh, friendly look.

Fran DiLeonardo, Director, IT Customer Service Management at National Grid, enthusiastically put his all into the project. “It was another great day making a difference in the community that we live and work in,” says DiLeonardo. “It’s always rewarding to put the time aside and make it happen; that’s why we keep coming back!”

Volunteers Bring the Energy

The Guidance Center was chosen for Project C this year by National Grid’s Alexandra Paoli, who was the onsite leader for the Day of Service at our Nature Nursery at the Marks Family Right from the Start 0-3+ Center (see cover story). She had learned of our mission through her mother, Michele Paoli, who has been with the utility for 25 years. The mother-daughter team, along with nine other National Grid volunteers, worked cheerfully and with gusto during the day-long beautification project.

“My mother knew about the great work of the Guidance Center,” says Alexandra. “When she suggested it be one of the sites of our statewide volunteer initiative, it was a natural choice.”

Making a Difference

Wisnewski credits National Grid’s staff for their devotion to the neighborhoods in which they live, work and raise their families. “Many of our employees have their own relationships with organizations in the community. Year-round, they do such remarkable things and make a real difference.”

National Grid plans to be back at the Guidance Center in 2023 for the next Project C Day of Service. “We know mental health is so important to all in our community, and it’s key to have places like the Guidance Center to help families and children on Long Island,” says Wisnewski. “National Grid is dedicated to investing in our youth, and we want to make sure we are doing everything we can to support the mental health of the next generation of leaders.”

We are so grateful to our friends at National Grid, and we’d love to partner with your company! Contact Lauren McGowan at 516-626-1971, ext. 320, to discover ways to help.

Main Photo: Our Leeds Place benefited from the wonderful volunteer efforts from National Grid.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Nov 7, 2022 | Blog

By Guest Blogger Colleen Stewart

There are pros and cons to the holiday season. It can provide a great opportunity to strengthen family bonds, reconnect with old friends, create new memories and enjoy delicious foods that only come around once a year. However, it can also be a source of intense emotional and financial stress.

Whatever experience you attach to the holiday season, there are ways to keep yourself calm and collected during the busyness of it all so that you can make the most of your time with loved ones. Here are some tips for de-stressing during the holiday season that will help keep you and your family happy and healthy.

Change your scenery

One great way to manage your stress during the holidays is to plan a getaway. U.S. News notes that a simple weekend excursion can bring big mental benefits, like reduced anxiety and stress. You don’t have to leave the city or state to have a rejuvenating vacation, either; it can be a simple trip across town. The important thing is that you give yourself a change of scenery, even if it’s just for a couple of days.

No matter where you live, you can find the perfect spot for a getaway. There are ample attractions and places to stay — even if you have to drive or fly. While a Disney trip may not seem like the most stress-free and budget-friendly way to remain calm, sites like Mouse Life Today can make putting together this sort of trip a lot easier and more affordable.

Take a breather

Another thing that can help with your stress levels is to take moments throughout each day to breathe and meditate. There are several breathing exercises that are simple and quick, and they can make a big difference in helping you stay relaxed. Also, practicing mindful meditation for a few minutes here and there can go a long way in helping you cope with stressful situations. If you struggle with making it a priority, Develop Good Habits suggests adding an app to your phone that will guide you through it and set reminders so you don’t forget.

Power up with a power nap

Long naps during the day can mess up your sleep habits. But short naps won’t do that—and they’re awesome! Taking a nap for 15 to 20 minutes in the middle of your day can make you more alert and improve your cognitive function and memory. In addition, it can also boost your mood and help you be more productive. For children, naps are a key to wellness. Check out this article for a guide to how much time is recommended,

Improve your bedtime routine

Speaking of sleep, you need plenty of it at night—seven to nine hours for adults, and more for kids, depending on their age. Otherwise, your mind and body won’t be prepared to function at full capacity each day, and you’ll be more prone to stress and anxiety.

If you find it difficult to get the sleep you need, change things up. Come up with a solid bedtime routine that helps you fall asleep and stay asleep, whether it’s taking a warm bath, listening to classical music, reading a paperback and/or doing relaxing yoga poses.

Add me-time to your morning

Along with taking a short daytime naps and getting a good night’s rest, consider waking up a little earlier than normal through the holiday season. It doesn’t have to be drastic; 30 minutes may be all you need to set positive intentions for the day. You could relax with a cup of coffee, write in a journal, read inspirational literature and/or anything else that helps you to collect your thoughts and get the day started off right.

Don’t try to do it all alone

The holidays are a busy time for most people, and sometimes there’s more stress than joy involved, particularly for those who don’t delegate well. It’s imperative that you do not take on every single holiday-related task on your own. Recruit your kids to help you with tasks you can offload, like helping to clean the house, walking the dog, etc. If you don’t already have one, now is a good time to implement an allowance system for your kids. You will feel better by having some help with holiday tasks, and your children will benefit from learning responsibility and the sense of satisfaction that comes from working to fulfill goals.

Make this holiday season the least stressful one yet. Go on a weekend getaway, practice breathing exercises and mindful meditation and take short daytime naps. Also, adopt a bedtime routine that helps you get the sleep you need, and allow yourself time to start off strong each morning. You may find that these simple tips have a profound effect on the well-being of you and your family amid the holiday bustle!

Bio: Colleen Stewart loves giving her two kids a healthy example to live by. Her passion for community and wellness inspired her and her husband to team up with their neighbors and create a playgroup that allows the adults and their kids to squeeze in a workout a few times a week. She created Playdate Fitness to help inspire other mamas and papas to make their well-being a priority, and set a healthy foundation for their little ones in the process.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Oct 31, 2022 | Blog

By Guest Blogger Andrea Gibbs

No one gets through life without experiencing one of the most difficult emotions to handle: rejection. It’s difficult watching our kids go through hard times and feeling like there’s little we can do to help them. But when it comes to rejection, it’s crucial that parents step in.

To be rejected by someone is one of the most uncomfortable feelings on earth.

Rejection can have long-lasting effects on young, developing minds. It can strongly affect a child’s self-esteem and can be linked to serious mental health issues.

Being rejected by a parent is especially difficult for a child. Parental rejection can happen in a variety of ways. Some parents simply don’t have time for their children; some are physically absent; some are distracted; and in the worst case, some are abusive.

Kids, as we all know, can be cruel, and when a child is excluded from a group of peers, it is very painful. This can be particularly difficult for children who are already experiencing mental health issues. Peer rejection can also cause stress and anxiety in children, leading to more serious problems as they age.

Children who experience peer rejection may have difficulty forming relationships with others later in life. These children tend to continue to feel rejected into adulthood.

Life event rejection occurs when a child experiences a major life-changing event, such as losing a loved one or a home. For example, if a child loses their pet, must move to another state or loses a grandparent or parent, they are likely to experience depression and anxiety.

They may also become more introverted and avoidant because they are afraid to get close to others to prevent another loss.

How Rejection Manifests

You may notice some of the following behaviors in your child when they experience rejection:

They may feel shame and be unable to admit their mistakes because they are afraid of being rejected or rejected by others. They may even feel guilty for all the negative things that have happened to them, which can lead to suicidal thoughts.

Children with low self-esteem may complain about stomachaches, headaches or other physical symptoms. They may think they are getting sick – or actually become ill – when they feel nervous or stressed.

Children who lack confidence struggle to believe in themselves and their ability to succeed. They tend to fear failure, so they give up on things before they even try, which leads them to fail in the end anyway. They are unsure of what they can do and may feel it’s not worth the effort.

A child who experiences rejection often focuses more on what others think of them than their own needs and wants. This can lead to self-harm, drug addiction, eating disorders and other dangerous behaviors.

Reduced self-care can also lead to high levels of anxiety. A child may feel overwhelmed with the responsibility of taking care of themselves, which leads to feeling too stressed to think rationally.

They may feel they are not worthy of having friends or being around other children. They may even begin to feel angry and upset because they do not have enough people who accept them as they are. This causes anger issues such as temper outbursts or aggression at others and toward themselves.

How to Help a Child Cope with Rejection

If your child is experiencing rejection, you can help them cope in the following ways:

- Encourage your child to be their authentic self

It is essential to encourage your child to be their own person. This will help them feel more confident in who they are, which will help them avoid feeling bad when they face negativity and criticism from others.

- Expectations

Make sure your child knows what you want from them and their role in your relationship. Give them responsibilities and tasks to complete that involve others in their life, such as attending a family function or volunteering at holiday time. This well also help build their self-esteem.

- Model Behavior

Your child will model their behavior after yours. If you are being kind and compassionate toward others, then they will learn to treat others the same way. If you are inconsiderate and rude to others, they will be selfish and disrespectful to others.

- Set Limits

Children need boundaries. Set limits on how they spend their time (especially when it comes to technology usage) and who they spend it with. This will help them follow your rules, as well as respect your opinions and wishes.

- Consider getting professional help

If your child is struggling with rejection, or you are having trouble helping them accept themselves, it may be time to seek out professional services from a therapist. Reach out to North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center at 516-626-1971.

Bio

Andrea Gibbs is the head of content management at SpringHive Web Design Company. This digital agency provides creative web design, social media marketing, email marketing and search engine optimization services to small businesses and entrepreneurs. She is also a blog contributor at Baby Steps Preschool, writing story time themes, parenting tips and seasonal activities to entertain children.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Oct 24, 2022 | Ask The Guidance Center Experts, Blank Slate Media, Blog, In The Media

In this monthly column, therapists from North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center answer your questions on issues related to parenting, mental health and children’s well-being. To submit a question, email communications@northshorechildguidance.org.

Question: Now that life has gotten back to some semblance of normal, my kids (ages 4, 9 and 11) are eager to go trick-or-treating this year. I’m thrilled for them, but the problem is that my little one is absolutely terrified of scary costumes.

As much as he wants to enjoy Halloween activities like his big brother and sister, he’s so frightened that I’m not sure we can take him out. He’s even said he doesn’t want to go to school that day. Any suggestions?

–Costume Conundrum

Dear Costume Conundrum: Halloween is one of the most exciting holidays of the year for youngsters. Candy, dressing up, parties at school—what’s not to love?

But your little one isn’t alone in his fear. For children around three to five years of age, and sometimes even older, the ghoulish costumes and yard displays can be overwhelming and very scary. But be assured, that’s a natural part of their development.

Luckily, most preschools and even elementary schools advise parents to avoid the scary kinds of costumes, so the schools themselves are typically safe zones. But once your son heads out to trick-or-treat, he’s likely to confront some frightening sights.

Of course, you know your son, so you’re the best judge of how scared he is likely to be. But as with all parenting issues, preparing ahead of time and anticipating any problems is the wisest strategy. Some tips:

- Let your son express his fears and reassure him in a calm voice that it’s OK to have those feelings.

- Play a game where your child scares you, and then laugh about it.

- Show him costumes online, so he’ll have an idea of what to expect.

- Do some crafts at home that create ghosts and other Halloween décor. Explain that any scary lawn displays are made of fabric and paint, just like the crafts you made together.

- Some children don’t like something like a mask covering their faces (even though they’ve had to deal with a different kind of mask for some time), so you might want to avoid costumes with masks.

- If he is frightened by costume masks on other people, put one on yourself and take it off to show him that you are still there!

- If your older kids are wearing potentially scary costumes, let your young one watch as they put on their makeup or masks, so he can gradually see how his big brother and sister transformed into the witch or warlock—and that it’s still them under the disguise.

- Make a visit to your local library and ask the librarian for books that help children see that Halloween is full of pretend things—some scary and lots of them just plain fun! One great choice: The Little Old Lady Who Was Not Afraid of Anything.

If your son loves his costume but when Halloween arrives, his mood changes and he refuses to wear it, try a compromise. Let him bring the costume to school instead of putting it on before he goes, or have him just wear part of the outfit. It’s definitely not something worth having a power struggle over, so if he refuses to wear it, let it go. It’s a perfect case of knowing when to pick your battles.

North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center, Long Island’s leading children’s mental health agency, is seeing clients both remotely via telehealth platforms and in person, depending on the clients’ needs. To make an appointment, call 516-626-1971 or email intake@northshorechildguidance.org.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Oct 18, 2022 | Blog

Volunteers Spruce Up Our Nature Nursery.

Young children learn important lessons through nature, and nothing beats hands-on experiences. That’s why we were so grateful when 11 employees from National Grid came to our Marks Family Right from the Start 0-3+ Center as part of their volunteer day of service, called Project C.

The volunteers spent the entire day planting, painting, repairing and whole-heartedly doing whatever needed to be done to spruce up the Nature Nursery at the Right from the Start Center, which had been left largely unattended during the pandemic.

“We are so grateful to all the National Grid volunteers for working so hard and with such great spirits to beautify our Nature Nursery and surrounding areas,” said Dr. Sue Cohen, Director of the Right from the Start Center, where the Guidance Center serves its youngest clients and their families. “The Nancy Marks Nature Nursery continues to provide our young children and their parents with an opportunity to enjoy their natural environment using exploratory, hands-on stations and activities, such as musical instruments, water, paints and graduated steps. Having a creative outdoor space to use during therapy and group sessions allows our therapists to engage children in a different way. The youngsters who have experienced this area love all that is has to offer and look forward to regularly returning.”

National Grid’s Alexandra Paoli, who was in charge of the project at the Guidance Center site, worked side by side with her mother, Michele Paoli, who has worked at the utility for 25 years. “Thousands of National Grid employees volunteer on this ‘Day of Service,’ which takes place at locations all across Long Island, upstate New York and New York City,” said Alexandra, a recent graduate of Penn State University and Associate Analyst, Community Customer Engagement. “My mother knew about the great work done at the Guidance Center, so when she suggested it be one of the sites of our statewide volunteer initiative, it was a natural choice.”

Therese Sullivan, National Grid’s Director of Operations Enablement, has participated in both Project C Day of Service events. “I was glad to volunteer for the Guidance Center because mental health is so important, especially helping children at an early age,” she said. “It is a great resource for families, and I’m proud that our company supports these efforts.”

If your company would like to discuss opportunities to volunteer at the Guidance Center or support our mission in other ways, contact Lauren McGowan at LMcGowan@northshorechildguidance.org or call her at (516) 626-1971, ext. 320.

Photo: A dedicated group of National Grid employees (pictured here with North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center staff) did an amazing job volunteering at the nonprofit’s Nature Nursery.

About North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center:

As the preeminent not-for-profit children’s mental health agency on Long Island, North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center is dedicated to restoring and strengthening the emotional well-being of children (from birth – age 24) and their families. Our highly trained staff of psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, vocational rehabilitation counselors and other mental health professionals lead the way in diagnosis, treatment, prevention, training, parent education, research and advocacy. The Guidance Center helps children and families address issues such as depression and anxiety; developmental delays; bullying; teen pregnancy; sexual abuse; teen drug and alcohol abuse; and family crises stemming from illness, death, trauma and divorce. For nearly 70 years, the Guidance Center has been a place of hope and healing, providing innovative and compassionate treatment to all who enter our doors, regardless of their ability to pay. For more information about the Guidance Center, visit www.northshorechildguidance.org or call (516) 626-1971.

About National Grid: National Grid (NYSE: NGG) is an electricity, natural gas, and clean energy delivery company serving more than 20 million people through our networks in New York and Massachusetts. National Grid is focused on building a path to a more affordable, reliable clean energy future through our fossil-free vision. National Grid is transforming our electricity and natural gas networks with smarter, cleaner, and more resilient energy solutions to meet the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

For more information, please visit our website, follow us on Twitter, watch us on YouTube, like us on Facebook and find our photos on Instagram

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Oct 11, 2022 | Blog

The weather may be starting to turn chilly, but it’s always a great time to enjoy the outdoors—and it’s also important for a youth’s development to keep their connection to our natural world.

With teens so immersed in texting and video games and other tech-focused pursuits, they often lose both the connection to each other and to the world around them. That’s why North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center designed our Wilderness Respite Program, which provides a unique opportunity for at-risk adolescents to participate in hikes and other nature activities that foster individual growth, leadership skills, self-esteem and friendships while also promoting environmental stewardship.

Teens who take part in the program often have issues such as depression, anxiety and ADHD. Many also lack the social skills that enable them to bond with their peers.

One of our clients who has made an incredible transformation as a result of the Wilderness Respite Program is James, who first came to the Guidance Center more than two years ago, James had no one to call friend. Even before the pandemic, James was isolated and lonely. His ADHD and anxiety made his behavior off-putting to others his age.

His parents were heartbroken; they were desperate to have their child feel welcomed and supported by his peers. While he got good grades, he viewed himself as a failure. School was just another place he felt like an outsider.

After starting individual and family therapy with one of our expert mental health experts, James joined the Wilderness Respite Program, which is made possible through the support of our generous donors.

During the hikes, James bonded with other teens in the program. They understood James, because many of them had the same challenges themselves. On trips to places such as Caumsett State Historic Park Preserve and Harriman State Park, teens learn how to be independent, as well as how to work together. It’s an incredibly affirming experience for kids who rarely get praise in school or other social situations.

James is no longer a sad and lonely teen with no friends to call his own. And he no longer feels like a “loser,” which is how he referred to himself when he first entered treatment.

Here is how the parent of another of our Wilderness Respite Program teens put it in a letter to the Guidance Center:

“My son started in the Wilderness Program about two years ago. I believe the program is the best thing he’s ever had. The Wilderness Program brings kids away from all the media; they go to nature, looking at natural scenery instead of a TV or computer screen. Talking with their peers, they do real human interactions while hiking. Sometimes it’s a long hike or challenging terrain, or even cold or hot or windy weather. It trains young people in endurance skills. The leaders of the trip are kind and always encourage the young people to keep going while they’re having fun.

This program has so many benefits for kids like my son, who has problems with social skills, making friends and anxiety. But every time he comes back from hiking, even though he’s tired and his feet hurt, he feels fulfilled and excited about everything he saw during his hike. It’s a great program!”

We are grateful to all of you who support our work and make the Wilderness Respite Program, along with our many other innovative initiatives, a reality.

Please reach into your hearts today and give as generously as you can.

Thank you for caring!

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Oct 4, 2022 | Blog

It was a trendy topic a few years ago, but it’s still a great idea!

The topic? Forest bathing, a method of self-care that goes far beyond its literal meaning of taking a bath in a forest. Forest bathing focuses on becoming one with your environment and the nature that is around you.

Here’s how Time Magazine put it:

“We all know how good being in nature can make us feel. We have known it for centuries. The sounds of the forest, the scent of the trees, the sunlight playing through the leaves, the fresh, clean air — these things give us a sense of comfort. They ease our stress and worry, help us to relax and to think more clearly. Being in nature can restore our mood, give us back our energy and vitality, refresh and rejuvenate us.”

Whether you call it forest bathing, hiking or simply a walk in the woods, spending time in nature is a great idea for the mental health and well-being of you and your kids alike. You don’t need to go far to immerse yourself in nature – find a local park or hiking trail in or around your community to get started. Plan wisely and be sure to pack comfortable shoes, sun protection and water. Being outdoors has many benefits, such as clearing your mind, reducing stress and reducing your blood pressure. It’s also a great excuse for your family to bond and to get off their electronics.

As useful as forest bathing is for personal and familial purposes, it is also deeply beneficial as a mental health intervention. North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center offers a program to at-risk youth which utilizes the theories that underlie forest bathing to help adolescents cope with stressors in their lives in our Wilderness Respite Program, which provides participants with a gateway to the mastery of social skills and youth empowerment through hikes and other outdoor activities.

As one of the parents of a Wilderness Program participant put it, “Therapeutically speaking, this program teaches my son the tools to handle his negative combative thinking through hiking in various land and weather conditions. During each hike my son participates in, I have observed positive changes in his attitude and behavior which last for several days. His thinking appears clearer, his mood swings lessen. This program has definitely increased his self-esteem. The benefits of this program are endless.”

To learn more about all the Guidance Center’s programs, contact us at 516-626-1971. Our trained clinicians can help you navigate any struggles that you may be experiencing.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Sep 27, 2022 | Blog

By Guest Blogger Colleen Stewart

Keeping your children and teens busy, especially indoors, can be quite the challenge if they’re always on the go. However, you can still make sure that learning indoors is as educational – and fun – as it would be outdoors, at school or anywhere else.

DIY Science Experiments

DIY experiments are a great way to keep curious young minds entertained for hours as they create and experiment with scientific equations and material. Furthermore, it could help them become even better at math and science because they’ll be putting theories into practice as the actual results unfold before their very eyes.

Board Games are an Excellent Option

Encouraging kids both young and old to participate in board games is a winner. After all, there are just so many varieties of board games to choose from that you’re sure to find one that will suit your child’s preference for the day. Moreover, most board games are designed to encourage their critical thinking skills and problem-solving abilities too.

Encourage Them to Try Their Hand at Cooking or Baking

Of course, this is one of those indoor activities that will require parental supervision. Nonetheless, it is an excellent opportunity to bond with your child while letting their creativity run loose. Furthermore, if your child battles with reading and comprehension, reading recipes out loud can help them identify words and understand sentence structure better, as well as help to improve their math skills when they learn how to measure ingredients and convert metrics.

Coloring

Coloring is also an excellent pastime, and it’s suitable for children of all ages. What’s more, it can improve your child’s fine motor skills, help them focus better and increase their attention span if they need help in this area.

Storytelling

Most kids relish the opportunity to hear a story from their parents, especially if it means undivided one-on-one attention with just you and them. But you can also step it up a notch by encouraging them to act out roles in a story to enhance their communication and language skills.

Keeping Them Entertained When You’re Busy

Suppose you work from home and need time without interruption from your kids. In this case, you could allow them to catch up on a bit of screen time, especially if it is educational. This way, you’ll be able to get your work done while they learn to keep themselves busy. Moreover, if you limit screen time to only a specific portion of the day, they’ll probably look forward to it more.

So, if you happen to be stuck indoors due to adverse weather conditions, be sure to take advantage of activities like these. That way, your kids won’t dread being cooped up inside, and neither will you!

Board games – https://bilingualkidspot.com/2019/06/18/fun-board-games-for-kids/

Recipes – https://www.bbcgoodfood.com/howto/guide/top-5-easy-bakes-kids

Coloring – https://www.learning4kids.net/2015/06/22/benefits-of-colouring-in-activities/

Story – https://www.splashlearn.com/blog/amazing-short-stories-for-kids-that-teach-beautiful-lessons/

Work from home – https://www.zenbusiness.com/blog/4-tips-for-working-from-home-with-young-kids/

Screen time – https://www.commonsensemedia.org/lists/educational-tv-shows-for-kids

Bio: Colleen Stewart loves giving her two kids a healthy example to live by. Her passion for community and wellness inspired her and her husband to team up with their neighbors and create a playgroup that allows the adults and their kids to squeeze in a workout a few times a week. She created Playdate Fitness to help inspire other mamas and papas to make their well-being a priority, and set a healthy foundation for their little ones in the process.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Sep 21, 2022 | Blog

Guidance Center client shares her journey from hurt to healing through Diane Goldberg Maternal Depression Program

This is the transcript of a speech given by Samantha Sutfin-Gray at the Guidance Center’s 2022 Sunset Soirée fundraiser, September 8, 2022.

My name is Samantha Sutfin-Gray and in June of 2021, I became a first-time mom, to a beautiful baby boy. Without the services from the Diane Goldberg Maternal Depression Program at North Shore Child and Family Guidance Center and the love and support from my husband and family, my son, Samuel, would not have a mother.

As a trained clinical social worker, I knew about Postpartum Depression and Anxiety. I knew the signs and symptoms; I knew what to look out for and I thought that my knowledge and education would protect me. I was wrong.

After having a high-risk pregnancy and a traumatic birth experience, I thought I had paid my dues and that I wouldn’t be one of the 1 in 7 women who experience Post-Partum Depression and Post-Partum Anxiety within the first year after giving birth. But I was wrong.

My symptoms started in just hours after giving birth. I was in a perpetual state of terror. I was convinced that I shouldn’t take my eyes off of my son or that he would stop breathing. It got to the point that I wouldn’t allow myself to sleep. I knew then that I needed help but when I asked for it, I was just told to take melatonin. With that sage advice, I thought that I was in this alone.

I was hopeful that once we left the hospital that my fears and symptoms would reduce, thinking naively that the hospital environment was to blame for everything. Through everything, I wanted to maintain hope that I could manage everything I was feeling on my own and being the perfect Mom that I had always envisioned being.

I muddled through for a few weeks trying to convince myself everything was ok. But things continued to get significantly worse. I knew the signs, intrusive thoughts, racing thoughts, inability to sleep despite crippling exhaustion, the feeling of inadequacy, thinking that my family would be better off without me, nightmares, and phantom cries. I thought I could beat it on my own. That if I was just a better mother that the symptoms would go away.

I obsessed over every part of Sam’s schedule, his sleeping, his feeding, how much I was pumping, even how much he was pooping, and any perceived deficiency would send me spiraling. I was never good enough because I could never control everything. From the outside perspective, I appeared to be the happy new Mom but internally, my mind was attacking me, sending me constant messages that I was never good enough. I was convinced that I was failing as a parent and that I was abusing my son because he cried, or because he didn’t finish a bottle or because he hadn’t pooped in a while and very quickly my thoughts turned to self-harm, to planning a way to kill myself or remove myself from my family because I was convinced, I was the problem.

I was trapped in the bottom of a hole that I couldn’t find a way out of.

It wasn’t until a Friday afternoon, about 6 weeks after I had given birth, where I spent the better part of the day strategizing how I could kill myself and make it look like an accident, that I came to the realization that I needed to get help.

I turned to North Shore Child and Family Guidance Center. From the beginning, they let me know that I mattered. That what I was going through was normal but that they understood that it didn’t feel normal to me. I was connected to a therapist, a psychiatrist, and a support group within days of making an initial call. I was welcomed into a community that understood what it was like to be a mom and was able to connect with other moms who had felt the same.

My therapist helped me understand that it was ok not to be Wonder Woman every day. She helped me to accept that even though I know the process, the diagnosis and definitions, I needed to ask for help and to manage my stress. She helped me to understand what I already knew that the hormones surging through my body were tricking my brain into thinking things that were quantifiably not true. And most importantly, she helped me remember that my family would not be better off if I wasn’t there.

I count myself as lucky. Because of my position in society, my understanding of mental health and the resources at my fingertips, I was able to find a program like The Guidance Center Not many women are in the same position as me. 1 in 7 women experience Postpartum Depression and Anxiety. PPD doesn’t discriminate by age, race, or class. It can happen to any parent and the effects can be devastating.

Postpartum Depression tears a person apart, it steals away the part of your soul that makes you who you are. During my darkest days, I loved my family unconditionally, but I couldn’t express it and I couldn’t see the devastation it was creating in my house. Postpartum Depression is an illness one person can have that the whole family suffers from. The Guidance Center’s Diane Goldberg Maternal Depression Program understands this. They created a treatment plan that addressed the functioning of my whole family and were able to help me repair the holes that my depression caused.

I can’t even imagine where I would be or how far my suffering would have taken me, if I hadn’t sought treatment on that Friday afternoon in July 2021, I probably wouldn’t have the pleasure to be standing here talking to you today. The Guidance Center helped me to see that there was a light at the end of a very dark tunnel, and they were with me every step of the way. For that, my family and I are eternally grateful. Every day, I get to watch my son grow and explore and learn new things and I don’t obsess about his poop nearly as much.

Thank you.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Sep 13, 2022 | Blog, In The Media, Newsday

Published in Newsday, September 12, 2022, Guest Essay By Kathy Rivera

I’ve been a social worker my entire adult life. I grew up in a household and a culture where talking about mental health was not allowed and mental wellbeing was not acknowledged or supported. The stigma was strong, but it only made me more determined to shed light on these issues and let people know it is perfectly normal to seek help.

But five years ago, when my then-15-year-old son came to me and said, “I don’t want to live anymore,” I was in total shock.

Not only was he having suicidal thoughts, he had also begun to formulate a plan—a prime indicator that the danger was real and imminent.

I felt overwhelmed because my child was hurting, and I also felt a deep sense of shame. How did I not see this coming? I had all the clinical knowledge to recognize the signs. It’s not that I didn’t know he had challenges. I just hadn’t realized it had reached a crisis point.

My family’s story is all too common, especially as young people struggle with the trauma caused by the pandemic. Children, teens and young adults have experienced the losses surrounding COVID-19 in deep and potentially long-lasting ways. Studies have reported sharp increases in rates of depression, anxiety, loneliness, and suicide attempts.

Trauma in children and teens is at an all-time high, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than a third of high school students said they experienced poor mental health during the pandemic; 44% reported feeling “persistently sad or hopeless.” One in five considered suicide; nearly 10% attempted it.

But the youth mental health crisis pre-dates the pandemic. In 2018, suicide was the second-leading cause of death among 10-to-24-year-olds, an increase of nearly 60% from 2007. Moreover, suicide rates among 10-to-12-year-olds increased nearly fivefold from 2010 to 2020.

Studies suggest that social media use and cyberbullying in particular contribute to depression, low self-esteem and other mental health issues that influence suicidal behavior, especially in girls. Tragic events such as mass shootings in schools have led to unprecedented levels of anxiety among youth. A lack of timely, affordable mental health care, economic struggles, and the epidemic of drug use also likely play a role.

While the picture seems bleak, there is a lot you can do to keep your child safe. Watch out for common warning signs of suicide, including withdrawing from friends and family, mood swings, engaging in risky or self-destructive behavior, changes in eating or sleeping patterns, increased use of drugs or alcohol, giving away possessions, posting suicidal thoughts on social media, and talking about death and not being around anymore.

We are lucky our son chose to tell us he was suicidal. We immediately sought professional help, and today, though he is not without struggles, he strives to maintain a balance with his mental wellness every day. We keep the lines of communication open, and assure him that we are there for him.

Ask your kids how they are feeling on a regular basis, even if they seem fine. Ask directly if they are having thoughts of suicide. Talking about suicide doesn’t make it more likely that they’ll consider the idea. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

Make talking about mental health the same as talking about any illness. We must all play a role in breaking the stigma and helping other children who may be hurting. Compassionate communication can save a life.

This guest essay reflects the views of Kathy Rivera, Executive Director and CEO of North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center in Roslyn Heights.

Kathy Rivera, Executive Director/CEO of North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Sep 6, 2022 | Blog

Long Islanders are very lucky to have one of the best public library systems in the country. In Nassau County alone, there are 54 libraries!

When you think of libraries, likely the first thing that comes to mind is (you guessed it) books—and being able to peruse thousands upon thousands of books at your library or at home is certainly a wonderful thing! But libraries offer a wide variety of services, some of which might surprise you.

Libraries are a real treasure for parents, children and teens. Most have preschool story times that foster early literacy, along with music classes and play time. They also have quiet study areas where students can do their schoolwork or meet up with their tutor (who may be a volunteer provided by the library). Many have book clubs for people of all ages, a great way to encourage love of reading and to meet new friends.

Adults and youngsters can enjoy a bunch of entertainment options, as many libraries host movies and music/theater performances. Art exhibits are another popular offering, which gives local artists a chance to exhibit their work. Arts and crafts classes are another popular option.

Libraries are great places to hear experts and take classes on a huge range of topics: preparing wills, tax help, learning Mah Jong, travel tips, writing your memoir, line dancing, yoga, defensive driving, job fairs, computer savvy, saving for college—the list is endless.

These days, most if not all libraries offer computer and internet access, which opens up a world of information to those who may not have access at home, or who may prefer to spend some time out of their house and in the warm embrace of their local library.

Librarians can help you find reference materials (whether paper or electronic) on a host of subjects, from career information to car repair to medical resources to town history—just ask and you will likely be given a great launching pad for your search into numerous interests.

If you love spending time at the library, there are many volunteer opportunities, such as reading to little ones, tutoring, helping new citizens learn English and much more.

So today, which is National Read a Book Day, make a trip to your local library!

Love Learning? Why not share that love by volunteering with the Guidance Center’s tutoring program? Please contact Lauren McGowan at (516) 626-1971, ext. 320, lmcgowan@northshorechildguidance.org.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Aug 30, 2022 | Blog

Here’s a great article on school bus safety, courtesy of safekids.org.

Riding the school bus for the first time is a big step for your child. Help your kids get a gold star in school bus safety by following these tips.

The Hard Facts about School Bus Safety

School buses are the safest way to get children to and from school, but injuries can occur if kids are not careful when getting on and off the school bus.

Top Tips for Riding the Bus

- Walk with your young kids to the bus stop and wait with them until it arrives. Make sure drivers can see the kids at your bus stop.

- Teach kids to stand at least three giant steps back from the curb as the bus approaches and board the bus one at a time.

- Teach kids to wait for the school bus to come to a complete stop before getting off and not to walk behind the bus.

- If your child needs to cross the street after exiting the bus, he or she should take five giant steps in front of the bus, make eye contact with the bus driver and cross when the driver indicates it’s safe. Teach kids to look left, right and left again before crossing the street.

- Instruct younger kids to use handrails when boarding or exiting the bus. Be careful of straps or drawstrings that could get caught in the door. If your child drops something, they should tell the bus driver and make sure the bus driver is able to see them before they pick it up.

- Drivers should follow the speed limit and slow down in school zones and near bus stops. Remember to stay alert and look for kids who may be trying to get to or from the school bus.

- Slow down and stop if you’re driving near a school bus that is flashing yellow or red lights. This means the bus is either preparing to stop (yellow) or already stopped (red), and children are getting on or off.

Learn More

Want more tips about how to keep your kids safe on or around school buses? Read more from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Aug 19, 2022 | Blank Slate Media, Blog, In The Media

Kindergarten Preparation, Published in Blank Slate Media, August 15, 2022

In this monthly column, therapists from North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center answer your questions on issues related to parenting, mental health and children’s well-being. To submit a question, email communications@northshorechildguidance.org.

Question: We have twins, a girl and boy, and both are entering kindergarten in September. This is a first for our family, and we’re not sure if we are doing enough to prepare them, especially since their pre-school experience was limited due to the pandemic. Any advice?

–Anxious Parents

Dear Anxious Parents: You’re not alone in having concerns about your children adjusting to the new routine of “big kid” school. Even before the pandemic, parents often felt anxiety about the transition to kindergarten, but since many families chose to keep their children home while COVID-19 was in full swing, those worries may be magnified right now.

Since many youngsters have been taught to keep their distance from strangers in order to avoid getting sick, they may be more wary of being with new people. You can help reassure them that you, their teachers and others are working together to keep everyone safe and healthy. While COVID-19 has shown itself to be somewhat unpredictable, we are in a far better place than we were a few years ago with preventative measures and treatment, and that information can be imparted to ease your child’s anxiety.

Starting in a new school can be scary under any circumstances, but there are steps you can take to help. If your school allows it, plan to bring your child to their classroom to meet their teacher before the school year begins. Also take them to see the gym, the playground, cafeteria, library, nurse’s office and other locations. Even if the teacher won’t be available, familiarizing your child with the school and the routine will go far in reducing their fears.

Be careful not to put your own fears onto your child. A lot of parents reflect on their own first-day jitters, and they assume their child feels the same way. While a certain level of school anxiety is entirely normal in children, they are also likely to feel excited, so remember to focus on the positive aspects of school, such as making new friends, having lots of time to play and learning fun new things.

Below are some more suggestions to make the transition as smooth as possible:

- Some schools help set up late summer playground events for incoming kindergartners. If they do, take advantage of the opportunity for your child to meet some new friends.

- Talk about what they are going to learn; make a game of “playing school” by introducing some of the activities that go on in a typical school day.

- Bring them with you when you shop for school supplies. Choosing their own folders, pencils, crayons and the like will make the experience feel special.

- Get your child on a regular bedtime schedule before school begins so they are accustomed to getting up at the same time they’ll need to awaken for school.

- Sit together and make a morning game plan—what are some breakfast ideas, which outfits will they want to wear their first week, and how they will be getting to school. If you can, do some practice runs (or walks) to the bus stop, if they’ll be taking one.

- Teach your child their basic contact information, including the correct spelling of their name, their address and their phone number. Also help them practice writing their own names.

- Make sure they know how to take their shoes on and off, and also how to zip up their backpacks.

When you give your youngsters a chance to talk about all their emotions and react calmly to whatever they say, it reassures them that everything will be fine. But if your child appears to be highly anxious and expresses reluctance to go to school after the first week or so, consider contacting a mental health professional. The pandemic has impacted children’s emotional well-being in numerous ways, so don’t hesitate to reach out for help.

North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center, Long Island’s leading children’s mental health organization, is seeing clients both remotely via telehealth platforms and in person, depending on the clients’ needs. No one is ever turned away for inability to pay. To make an appointment, call 516-626-1971 or email intake@northshorechildguidance.org.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Aug 15, 2022 | Blog

Earlier this summer, North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center was excited to announce that our Children’s Center at Nassau County Family Court had reopened after a two-year hiatus due to the pandemic. During that time, almost all court business was conducted virtually, but with more and more children and families returning to in-person court visits, our Children’s Center is a much-needed community resource!

With family court matters such as divorce proceedings and custody cases often very contentious, youngsters can be traumatized if they are in the courtroom. But many parents and guardians don’t have the luxury of leaving their children home.

That’s what makes our Children’s Center at Nassau County Family Court so important. At the Children’s Center, kids from 6 weeks to 12 years old are provided with free care in a nurturing and safe early learning environment while adults are busy in court.

How can you help? We are seeking volunteers at the Children’s Center, which is located at 1200 Old Country Road in Westbury. To volunteer, we request that you are…

- 16 years of age or older

- Fully vaccinated against COVID-19

- Able to work a minimum of four hours per week

- Comfortable wearing a mask

- Willing to complete a NY State background check, including fingerprinting

- Able to lift children when necessary and have good mobility

- Friendly and nurturing

Volunteering at the Children’s Center is a great way for high schoolers (16 and up) or college students who have an interest in children and education to gain experience! And it’s also a wonderful opportunity for anyone who loves kids to give back and make a difference for the youngsters and families in our community.

To learn more about this fulfilling volunteer opportunity, contact Dr. Nellie Taylor-Walthrust at 516-997-2926, ext. 229, or email ntaylorwalthrust@northshorechildguidance.org

Benefits of Volunteering:

- It reduces the risk of depression by helping you make new friends and building a support network.

- It boosts your self-esteem and helps you develop better communication skills.

- Volunteering helps you stay active and engaged with the world, and depending on what kind of volunteering you do, it could even help you stay more physically fit, including lowering your blood pressure!

- It exposes you to new experiences, giving you insight into the world around you and all the opportunities that are out there just waiting for your energy and dedication.

- It helps reduce stress and loneliness by providing you with a feeling of purpose and connection.

- The symptoms of mental health issues such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, anxiety and other conditions have been shown to decrease when people volunteer.

- Volunteering gives you perspective, helping you realize that there are others in the world struggling with issues, just like you.

- The bottom line: Volunteering is fun!

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Aug 9, 2022 | Anton Media, Blog, In The Media

By Erika Perez-Tobon, Published in Anton Media Newspapers

One of North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center’s signature programs is the Latina Girls Project, which was created in response to the alarming rates of depression, school refusal, self-harm, suicidal ideation and attempted suicides by Hispanic teen girls.

More than a decade ago, our team at the Guidance Center noticed an increasingly large number of first-generation Latinas were coming to us with severe depression, self-harming behaviors and suicidal thoughts. Many had stopped attending school, and some had been hospitalized for suicide attempts.

The research backed up what we were seeing at the time: Hispanic teenage girls were significantly more likely than their non-Hispanic peers to suffer from depression, thoughts of suicide and suicide attempts. More recent research, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, showed that 10.5% of Latina adolescents aged 10–24 years in the U.S. attempted suicide in 2016, compared to 7.3% of white female, 5.8% of Latino and 4.6% white male teens.

In response to this crisis, we formed the Latina Girls Project, an innovative program that employs individual, group and family therapy, along with monthly outings and other activities, all designed to tackle issues such as depression, low self-esteem, social anxiety, school refusal, self-harming behaviors or suicidal ideation.

Some of our clients who were born outside the U.S. have witnessed violence in their homelands, and many have experienced complex trauma since a young age. Those who were born in the U.S. are impacted by the generational trauma experienced by their parents and limitations around communicating with their parents.

Regardless of where they were born, a big part of the reason these girls are struggling is because they are pulled in conflicting directions, with their parents wanting them to adhere to the traditional values of their homeland, while the girls seek to integrate into American culture and find acceptance among their peers.

The result: Parents are often extremely overprotective; they won’t allow their daughters to venture out and participate in activities such as sleepovers, dating or trips to the mall. Even if the teens are allowed to go out with their friends, they are required to have a chaperone, such as a parent or brother. In addition, they are often relegated to gender-biased roles, required to cook, clean and take care of their siblings while their brothers are treated, as one girl said, “like princes.”

During bilingual individual, family and group therapy sessions, the girls realize that they can trust their therapists, many of whom also grew up as first-generation Latinas. The therapists teach the girls healthy strategies to deal with stress and depression and effective ways to communicate with their parents.

For their part, the parents become more compassionate about their daughters’ desire to fit in, and they also understand the need to let their teens separate in age-appropriate ways. One of our Latina clients put it this way: “My parents learned that I just wanted them to be there for me and listen. They learned that it doesn’t help to question why I feel the way I do but to accept it and support me.”

In addition to therapy, the program incorporates monthly supervised outings to places such as theaters, museums and other cultural and educational sites. These trips, made possible by the generosity of John and Janet Kornreich, expose the girls to the world in a way that would never have happened if not for this Guidance Center program. The trips serve to boost the teens’ confidence and sense of independence, and the girls also discover that there’s a great big world of opportunity out there for them, which allows them to feel hopeful about their futures. The trips also offer respite to the parents who are relieved to know that their daughters are in safe hands.

As one girl put it, “The Latina Girls Project helped my mother and I communicate and become very close, and the monthly outings showed me a world I never would have seen. I felt that I wanted to be a part of the larger world. The trips gave me the feeling that I could be truly happy in my life.”

Bio: Erika Perez-Tobon, LCSW, who is originally from Venezuela, is the bilingual Clinical Supervisor of North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center’s Latina Girls Project, which is located at the agency’s Westbury location.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Aug 2, 2022 | Blog

By Colleen Stewart, Guest Blogger

A child’s success throughout life can depend on the level of emotional support from parents and caregivers. These suggestions promote positive self-care behaviors that last a lifetime.

Foster Open Communication

A weekly family meeting gives every member time to express concerns and address tensions so that issues don’t fester under the surface. Feeling heard and understood is an essential human need and the foundation of solid relationships. Keep to a set time limit and take care not to let disagreements devolve into bitter arguments.

If possible, attempt to have one meal together daily where the emphasis is on being a good listener. Help your kids see the value of listening by demonstrating balanced conversational techniques and teaching them how doing so creates healthy friendships.

Enjoy Recreational Events

Help your little ones relax by going to a game of the family’s favorite sports team. Enjoy some tasty treats and pick up souvenirs for treasured lifelong memories. Make it a weekend getaway if you have to travel more than a couple of hours to get to the event. For instance, if you’re wondering how to score Yankees or Mets tickets, search online and sort by date, price range and seat rating. Check the seller’s site for an interactive seating chart to see a 360-degree view from your seats ahead of time. And when you get home, continue the fun by playing catch with your kids!

Unwind with a day at the zoo or a walk in the woods. The natural setting can be a calming form of therapy, but prepare to adjust plans if your child becomes unsettled by specific animals. Read a book or visit a website teaching about the types of animals present to assuage fears.

Volunteer as a Family

Instill high moral values in your children by devoting time to assisting others and strengthening the community. At least an hour or two each week should be spent on volunteer activities. Encourage the kids to sign up for helpful groups and earmark time for giving in their personal schedules.

Set a Good Example

Model self-care. Study after study confirms that stress is contagious and alters how human brains work, leading to other physical and mental illnesses. Create self-care goals that the family tackles together.

Prevent outside influences from disrupting the peace of the family. Doing so can be especially challenging for business owners, so establish boundaries. Family members must agree to allow you time during the workday to focus on your company without unnecessary distraction. In return, set times where you focus on the family and silence all professional alerts and messages. Relegate intensive tasks to the morning when you’re fresh and can give them resolution before the day’s end. Don’t micromanage the business and delegate mundane assignments where possible.

Consider Counseling

A child overwhelmed with stress and anxiety can benefit greatly from regular counseling at North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center, which is now offering both in-person and virtual therapy.

Bottom line: Reducing stress through a variety of means is worth the effort, so collaborate to give your children a self-care routine that helps them refresh, reset and ready themselves for life’s challenges.

Bio: Colleen Stewart loves giving her two kids a healthy example to live by. Her passion for community and wellness inspired her and her husband to team up with their neighbors and create a playgroup that allows the adults and their kids to squeeze in a workout a few times a week. She created Playdate Fitness to help inspire other mamas and papas to make their well-being a priority, and set a healthy foundation for their little ones in the process.

by North Shore Child & Family Guidance Center | Jul 25, 2022 | Blog

By Alex Levitt

As Reported in Insight into Diversity, “This July marks the 14th annual observance of BIPOC Mental Health Month, previously known as National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month. The observance comes at a critical time as concerns regarding psychological and emotional well-being are at an all-time high for young people and students, especially those from underrepresented communities.”

An ample collection of research on Mental Health America. has demonstrated that the educational, economic and social turbulence caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the epidemic of anxiety and depression among youth. For young people of color, these repercussions have been magnified by racial violence and discrimination. Yet this population is less likely to seek out psychological support services due to “the high costs of mental health care, the social stigma associated with seeking treatment, a lack of access to culturally competent counselors and a general mistrust of medical professionals.” (Insight Staff, 2022)